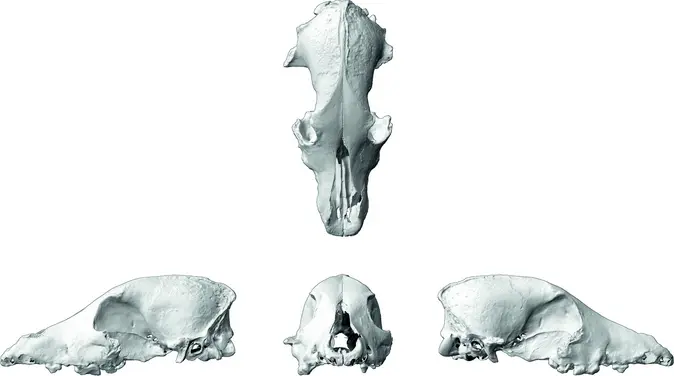

Skull of the 4,700-year-old Neolithic dog prior to complete genome sequencing

Cranial scan of the Kirschbaumhöhle dog

The skull was found in the Kirschbaumhöhle (Cherry Tree Cave) in the Frankenalb region of Germany.

One Place, One Domestication Process

Seven years after the discovery of the only untouched pit cave discovered in Germany to date – the Frankenalb region’s Kirschbaumhöhle (Cherry Tree Cave) – the cave continues to provide valuable scientific insights. The bones, and particular the skull, of an approximately 4,700-year-old dog have become a focus of an international research project involving the University of Bamberg’s department of Prehistoric and Protohistoric Archaeology. Researcher Dr Timo Seregély is heading the department’s efforts.

Using DNA analysis of both the dog from Neolithic Kirschbaumhöhle and another prehistoric canine bone from Herxheim in the Palatinate region, researchers at Stony Brook University in New York and at the University of Mainz have determined that the dogs’ genomes almost certainly represent the ancestors of modern European dogs. The study also suggests that all modern dogs share a common geographic origin and emerged from a single domestication process of wolves that occurred between 20,000 and 40,000 years ago.

"Contrary to the results of previous studies, we found that our ancient dogs from the same time period were very similar to modern European dogs, including the majority of throughbred dogs people keep as pets," explains project director Dr Krishna Veeramah from Stony Brook University. “This suggests that there was likely only a single domestication process for the dogs observed in the Stone Age fossil record and that we also see and live with today.” The dating of these newer samples also differs from previous findings; older studies placed the domestication process between 19,000 and 32,000 years ago.

Exact geographic origin still unknown, but confined to one region

Researchers have been unable to determine the specific place in Asia or Europe where the transition from wolf to dog occurred, but according to the most recent findings, it likely occurred in a single region. Dr Seregély led the archaeological investigation of the Kirschbaumhöhle and discovered skulls and other bones of two humans dating from the same period. Examination showed that these two humans, or their direct ancestors, most likely migrated from East-Central Europe. With regard to genetics, the dog represents a cross between European dogs and a population resembling modern Asian/Indian street dogs. Seregély explains that, “At the transition from the fourth to the third pre-Christian millennia, significant societal and ideological upheaval originating in the Yamnaya culture of the Pontic steppe gave rise to new prehistoric cultures like the Corded Ware culture of eastern Central Europe. Genetically, it has been verified that migration played a crucial role in this development. We therefore postulate that migrant Corded Ware settlers brought their animals with them – which accounts for the Asian genetic component.” However, determining a more exact origin of canine domestication would require a larger sample of bone material from the Palaeolithic period. To date, the oldest remains of dogs that can be conclusively distinguished from those of wolves originate from what is now Germany and are around 15,000 years old.

Plans for further excavations and DNA analyses

The Kirschbaumhöhle will remain an enormously significant resource for future archaeological and palaeogenetic research. “Because the cave remained buried following its last use in the Iron Age, roughly 760 – 400 BCE, and was discovered completely untouched, preservation conditions for animal and human DNA are excellent,” says Seregély. “Moreover, we’ve already discovered bones originating from three different periods: the Stone, Bronze, and Iron Ages. These can provide a wealth of information on about 4,000 years of cultural history.” In the next phases of research, Timo Seregély and the palaeogeneticists from New York and Mainz will expand their focus beyond dogs to include bovine and human bones found in the cave. Several DNA analyses are planned for the near future, including ones aimed at gathering new data on the origins and population history of humans and domestic animals.

The study on canine domestication was published in Nature Communications.

This article was translated by Benjamin Wilson.