In the chapter entitled “Using ‘small’ corpora to document ongoing grammatical change”, Christian Mair demonstrates via his corpus-based case study on specificational cleft constructions that “small” corpora can nowadays still be useful for corpus linguists, despite the existence of much larger and therefore often more representative collections of texts.

In the introduction, Mair explains the double advantage of corpus material for linguistics. Corpora usually contain a big quantity of data and allow the use of the quantitative approach. Additionally, linguists get access to authentic examples in context, which enables them to use the qualitative approach. Thus, a combination of both of these methods is particularly useful for the analysis of “small” corpora.

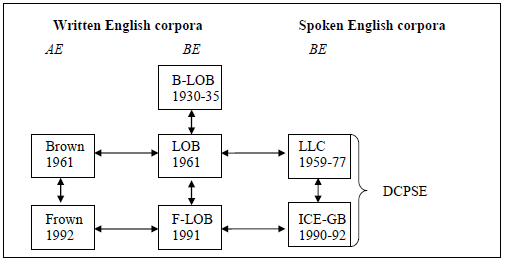

The case study on specificational wh-cleft constructions is based on seven comparable corpora which can be divided up into five written English and two spoken English ones. Regarding the written English corpora, a further distinction between those of British English and those of American English is necessary. By working with B-LOB (1930-1935), LOB (1961) and F-LOB (1991), the author is able to illustrate the development of specificational clefts within the British variety. The supplementary use of the American English corpora Brown (1961) and Frown (1992) enables him not only to see how the clefts have developed in the American variety, but also to draw a comparison between the two varieties. Concerning the spoken English corpora, Mair uses the Diachronic Corpus of Present-Day Spoken English (DCPSE), comprising the British English corpora LLC (1959-77) and ICE-GB (1990-92). Hence, the DCPSE makes it possible to show changes in the use of clefts in the spoken British variety. Furthermore, a comparison between spoken and written British English becomes possible, as LLC and ICE-GB are approximately comparable with regard to their time depth to LOB and F-LOB respectively (cf. Chart 1).

Chart 1: Comparability of the seven corpora used for the analysis (cf. Mair, Chapter 9)

The case study is presented along with the steps needed to obtain good and valid results when carrying out corpus analyses. Mair analyzes specificational cleft constructions and more precisely the variation between to-infinitive and bare infinitive in those sentences (cf. 1a and 1b).

(1)

a. “What I did was to help him find a new job.” (Mair, Chapter 9)

b. “What I did was help him find a new job.” (Mair, Chapter 9)

He hypothesizes that the English language has developed from a phase in which the speakers could only use the to-infinitive in the specificational clefts into the current period, in which both the to-infinitive and the bare infinitive are in use and compete with each other. This development will continue to a final stage in which the to-infinitive will be replaced with the bare infinitive.

Before finding out whether this assumption is true, the author defines the variable more precisely by using explanations from different grammars. He then decides to restrict the analysis to four types of wh-cleft constructions, namely the ones containing a to-infinitive, a bare infinitive, an –ing form or a finite clause. Each of the variants is illustrated with corpus examples (cf. 2–5).

(2) “All you need to do is to remember the four names[.]” (LOB F; Mair, Chapter 9)

(3) “[A]ll that people have done is put a sort of pretty wrapping[.]” (DCPSE: ICE-GB; Mair, Chapter 9)

(4) “[A]ll it’s doing is keeping the sheep in this field from going onto that one[.]” (F-LOB F; Mair, Chapter 9)

(5) “What they’re doing is they’re working on the <,> Pascal thing [.]” (DCPSE: ICE-GB; Mair, Chapter 9)

The author’s search procedure in the corpora is to combine the forms of the verb do, thus, do, did, does, doing and done, with is and was. With this strategy, precision is quite high and recall is very high, as only few sentences like those including complex forms of be are not retrieved in the search.

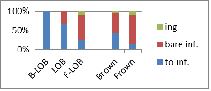

Regarding the corpora of written English, the following three major results are obtained (cf. Chart 2):

1) All the examples in B-LOB contain a marked infinitive.

2) While the to-infinitive was still used more often in the 1960s, the bare infinitive is preferred in written British English in the 1990s.

3) There is a great probability that American English has been the precursor of this reversal.

Chart 2: Complements in specificational clefts in the corpora of written English (cf. Mair, Chapter 9)

Furthermore, it is possible to deduce the diachronic trends for 20th and 21st century written English. Specificational clefts with a marked infinitive will be replaced by clefts containing a bare infinitive. However, if the cleft is preceded by a verb in the progressive aspect, the marked infinitive is substituted by an –ing form.

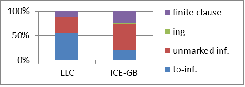

The reversal of preferences from the use of a marked to an unmarked infinitive is also visible in the corpora of spoken British English and seems to have taken place at approximately the same time in the spoken and written varieties (cf. Chart 3).

Chart 3: Complements in specificational clefts in the corpora of spoken English (cf. Mair, Chapter 9)

Consequently, the outcomes of the corpus analysis show that Mair’s hypothesis is valid and that there is ongoing grammatical change from a marked to an unmarked infinitive in the English language regarding wh-cleft constructions.

The linguist concludes the chapter with an enumeration of positive aspects and possible drawbacks of “small” corpora in their use to document ongoing grammatical change.

Created with the Personal Edition of HelpNDoc: Easily create iPhone documentation