Multi-dimensional analysis is a corpus-based and computer-supported statistical technique to provide a comprehensive analysis of register differences. Since this methodology requires special computer programs not available for every student, a small-scale analysis of registers seems appropriate. The present section will therefore offer an outline of the major steps to be taken when examining registers manually. A complete instruction to register analysis along with useful exercises and examples is to be found in Biber and Conrad 2009.

Biber and Conrad emphasise that three main components should be taken into account when scrutinising registers. The first is represented by the situational characteristics influencing the choice of a register (cf. Biber and Conrad 2009: 6). Since registers are generally defined by their situational context, the investigation of this aspect seems most important. Secondly, registers can be differentiated by the distribution of their pervasive linguistic and grammatical features. It is assumed that each register feature represents a certain function to match the situational context. The third component is thus the identification of the functions that link the features to the purpose of the situation (cf. Biber and Conrad 2009: 6).

After having identified the registers to be studied comparatively, I started the examination with an analysis of the situational context. There are several sources that might help identifying the characteristics: you might either rely on your own experiences and observations, depending on how involved you are with the registers, or otherwise resort to expert information and previous studies, as well as looking at the texts as such (cf. Biber and Conrad 2009: 37-39). To facilitate the initial analysis, Biber and Conrad provide a general framework (see Table 3) to be applied in the study. However, not all characteristics are equally important for every analysis.

|

a) Is time and place of communication shared by participants? b) Place of communication à private/ public, specific setting c) Time à contemporary, historical time period |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3: Framework for situational analysis (Biber and Conrad 2009: 40)

To illustrate the procedure of register analysis, I carried out a small-scale study. The study is concerned with the comparison of two quite general registers found in every-day life of students of English: novels and newspaper articles. The situational analysis, which is illustrated in Table 4 below, is based on the framework of Biber and Conrad, including information provided in Biber and Conrad 2009 as well as my own experiences and observations:

Situational characteristics |

Novels |

Newspaper articles |

Participants Addressor Addressee |

usually single author general group |

may be single, plural, institutional or unidentified, adult journalist general group |

Relations |

no interaction, shared knowledge of plot, setting, characters etc. |

no interaction, shared knowledge varies |

Channel |

written, printed |

written, printed or online |

Production and comprehension circumstances |

carefully planned and revised production often without space or time constraints may be read for enjoyment or to analyse literary characteristics |

time for planning, revising, editing, often with deadlines and space constraints different reading modes – skimming or careful reading |

Setting |

no shared time or place public, can be read by a wide audience contemporary (in this study) |

no shared time or place, expected to be read on day of production public, may be associated with a special city or region contemporary (in this study) |

Communicative purposes Factuality Stance |

narrative, telling of stories, for entertainment fictional events and characters, imaginary rarely overt expression of opinion, attitude of fictional characters is exposed |

informational, reporting of events, analysis and discussion factual reports without personal attitudes of author not overtly expressed |

Topic |

varies according to story and sub-registers, e.g. mystery, romance, horror, fantasy... |

current events and news in many different areas of interest, e.g. economy, sports, education... |

Table 4: Situational analysis (cf. Biber and Conrad 2009: 111-112)

The examination of the situational characteristics indicates that the external aspects concerning participants, channel, setting or production circumstances do not differ significantly. In contrast, the internal factors of purpose and topic represent a central divergence which most probably will influence the pervasive linguistic features of the registers.

Following the situational analysis, the second step is to find out the features that are typical of the register. This task is often rather complex, especially when the student is not familiar with the register. This time, relying on experience does not suffice. Therefore, the study is in need of a comparative approach, a quantitative analysis as well as a representative sample (cf. Biber and Conrad 2009: 51). That is, the initial assumptions concerning the features to be studied should be checked carefully by comparing the respective register texts (cf. Biber and Conrad 2009: 52). Furthermore, the quantitative approach is necessary because the features have to be more frequent than in other registers, that is the occurrences of the features have to be counted and then compared once more to other texts (cf. Biber and Conrad 2009: 56). Finally, a representative sample is necessary because the generalisation from a single text to an entire register is not possible. That is, the chosen texts need to be diverse in speakers or writers and all sub-registers have to be included (cf. Biber and Conrad 2009: 58). Once more, this is a difficult task since all features have to be counted manually and therefore a small-scale study cannot include the same amount of texts as corpora do and is thus not representative enough to characterise registers completely, but offers a basis for further analysis. In this study, two rather general registers are examined. Therefore, the texts have been chosen as varied as possible, including several sub-registers, topics and authors (For the final selection see appendix.).

When conducting a quantitative analysis, it is essential to provide an accurate identification and categorisation of the linguistic features and to choose them carefully. It is indispensible to decide on a justifiable classification of the features and to apply the decision systematically to all relevant cases (cf. Biber and Conrad 2009: 59). In contrast to multi-dimensional studies, the decision which features are pervasive is taken ahead of the analysis, instead of being identified statistically (cf. Biber and Conrad 2009: 225). In the present study, ten features have been chosen to be examined in the texts: finite verbs, nouns, nominalisations, pronouns, place and time adverbs, passive verb forms, prepositional phrases modifying nouns, public verbs, to-infinitive clauses and that-complement clauses. The decision was taken based on the information provided in Biber and Conrad 2009 and my own observations. Biber and Conrad refer to the Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English, which provides a thorough description of linguistic features that are pervasive in four general registers (cf. Biber and Conrad 2009: 63). However, the counting of occurrences can be problematic since this procedure requires thorough linguistic knowledge and expertise to correctly distinguish for example between pronouns and determiners, adverbs and prepositions etc.

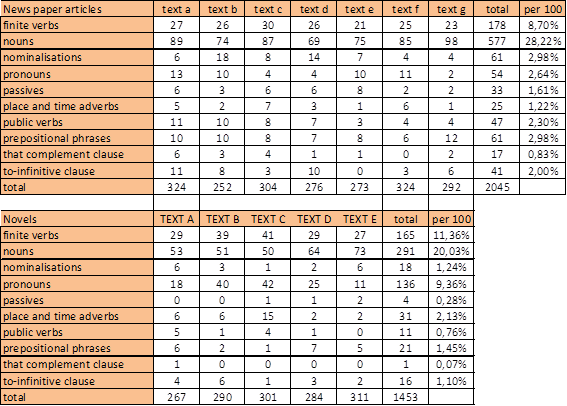

Following the quantitative analysis, the raw frequency counts have to be normalised in order to enable an accurate comparison across texts. That is, the raw counts should be divided by the total number of words and then multiplied with a chosen basis, e.g. occurrences per 100 words (cf. Biber and Conrad 2009: 62). For instance, in the present study, newspaper articles contained 178 finite verbs of 2045 words in total, whereas novels included 165 on a total of 1453:

(raw count / total word count) * 100 words = normed rate (178 verbs / 2045 words in total) * 100 words = 8.7 verbs per 100 words (165 verbs / 1453 words in total) * 100 words = 11.36 verbs per 100 words |

The results of the frequency counts and the normed rates are represented in Table 5:

Table 5: Frequency counts and normed rates

The final step of register analysis is to match the two previous descriptive investigations and thus interpret the functions represented by the linguistic features. As noted above, the most significant situational difference is the purpose of communication, which is either narrative or informational. This distinction is reflected by the frequency counts, particularly well by pronouns, verbs and nouns/ nominalisations. Since the major purpose of newspaper articles is to convey information, along with place constraints, many pervasive features are associated with informational density. Especially nouns and nominalisations are common for the integration of precise information as well as to-infinitive clauses and prepositional phrases to modify and further specify nouns. In contrast, in novels the main focus is narrative, describing actions and scenes, and therefore this register includes many verbs. Additionally, the high frequency of pronouns, which generally refer to something that is known, reflects the shared knowledge of author and reader concerning the contents of the story. This aspect is also represented by place and time adverbs such as there, here, now etc. Newspaper articles also refer to entities mentioned before, but since the informational style requires precise noun phrases, pronouns occur rarely. Despite the low overall frequency of verbs, articles include a large number of public verbs often linked with that-complement clauses, which obviously serve the integration of attitudes and statements of persons other than the author. Novels rather express the personal feelings and thoughts of the characters and thus make minor use of public verbs. Furthermore, events are typically expressed actively in novels to stress the acting person, whereas newspaper articles use a passive style to avoid mentioning the agent and to stress the event.

This small-scale study thus shows that even by means of a small number of texts and register features, major differences between registers can be revealed and used as a starting point for further analysis. Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind that the results of a small-scale analysis are preliminary and therefore not suitable for generalisations (cf. Biber and Conrad 2009: 75).

Created with the Personal Edition of HelpNDoc: Free help authoring tool